My reasons for writing a follow-up to Moneyball are many. The tagline of the book in 2003 was "The Art of Winning an Unfair Game." In many ways, the tagline still applies today.

The fiscal model for modern day Major League Baseball favors the rich and hinders the poor. It is the only major league sport in the United States that does not have a salary cap. It is the only one that has individually negotiated television rights deals. It's the only one with an antitrust exemption. And it's arguably the only sport that has venues that are perhaps more of a draw than the teams that play in them.

In those departments, the Oakland Athletics are 0-for-4.

With four strikeouts.

The Golden Sombrero.

SALARY CAP:

In the spirit of fair play, the National Football League, National Basketball Association, and even Major League Soccer have all adopted salary cap provisions. What fun, the argument is, would it be to see the Dallas Cowboys gobble up all of the talent from teams with less resources? Imagine a universe where Drew Brees (New Orleans) is throwing 65-yard touchdown bombs to Calvin Johnson (Detroit), or handing the ball off to Adrian Peterson (Minnesota). That's great for the Cowboys. Not so much for the Saints, Lions, or Vikings. The salary cap is there for the greater good. Theoretically every team has a chance at winning every year.

No such rule exists in baseball. The Los Angeles Dodgers can have a payroll of $233 million. The Houston Astros? $45 million. That's a difference of nine players making $20 million a year. Or, you know, an entire team on the field.

TV DEALS:

Every Sunday, you can watch your favorite NFL team on the tube. Or on a Thursday or Monday night if you're lucky. But you won't be watching that game on your local cable channel. You're watching it on national broadcast television, FOX or CBS on Sundays. NBC on Sunday nights. ESPN on Mondays. NFL Network on Thursdays. Those broadcast rights deals, it should be noted, are negotiated by the NFL on behalf of its owners. For those of you keeping track,

that's a cool $27 billion -- yes, billion -- split evenly among the NFL's 32 teams.

Baseball is making big bucks on television as well, but only a select few are seeing the billions instead of millions. You can literally count on one hand the number of MLB teams with a television deal that totals a billion dollars or more.

The L.A. Dodgers are at the top of that list with an annual rake of anywhere between $240 to $280 million per season. The teams at the bottom of the list make less than $20 million annually.

ANTI-TRUST EXEMPTION (LOCATION, LOCATION, LOCATION):

There are antitrust laws in the United States that prevent businesses from monopolizing a given market. As consumers, we have the right to choose between Verizon and Sprint. DirecTV and Dish. Coke and Pepsi. But if you thought Major League Baseball was bound by those same antitrust laws, you would be wrong.

With the help of the Supreme Court,

Major League Baseball has held on to its title as the only true monopoly in the United States. You can thank Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis for that. In 1915, he ruled on a lawsuit from the Federal League that claimed Major League Baseball had interfered with its attempts to sign players who were not under contract. Do you think Landis, a huge fan of the Chicago Cubs, ruled in favor of the Federal League? Would you be surprised to hear that Landis was later selected as the first Commissioner of Major League Baseball?

The antitrust exemption has benefited Major League Baseball by stamping out potential competitors. The National Football League, though, has received no such exemption and has battled upstarts like the USFL and XFL within the last couple of decades, forcing the NFL to stay on top of its game. Whoever said competition is good for business forgot to tell Major League Baseball.

Competition isn't even welcome within its own ranks in baseball. MLB owners have threatened lawsuits to prevent teams from expanding in what they believe to be "their" territory. Orioles owner Peter Angelos fought for years to keep teams from relocating to Washington, DC, a market that is one hour away from Baltimore. Nevermind that the Cubs and White Sox share Chicago. Or the Dodgers and Angels co-exist in Los Angeles. Or the Yankees and Mets are roomies in New York. Angelos eventually lost his battle, but only after MLB forced the new tenants in DC, the Nationals, to sign a 30-year TV deal with the Mid-Atlantic Sports Network (MASN). Angelos just happens to own 90% of MASN, which now broadcasts Nationals and Orioles games.

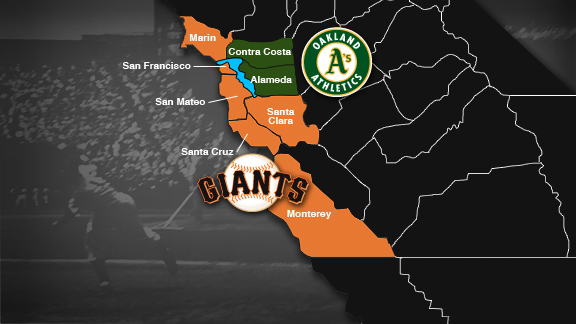

The A's are now in a very similar fight in Oakland. Although they play in the Bay Area,

they are essentially a housemate renting out a small room in a much larger house occupied by the Giants. The Giants have territorial rights to not only San Francisco -- the most populous city in the Bay Area -- but also the counties of Santa Clara, San Mateo, Santa Cruz, Marin, and Monterey. The A's? They get Alameda and Contra Costa. That's it.

Amazingly, the A's conceded these South Bay Area territories to the Giants in the late 1980's when the franchise was on the verge of relocating to St. Petersburg, Florida. An 11th hour deal was struck between the two franchises to allow the Giants to explore new stadium sites in the South Bay. The A's received zero compensation for surrendering these rights to what was considered at the time a shared territory.

Now, three decades later, the city of San Jose is suing Major League Baseball to allow the A's to move south from Oakland in what is purportedly San Francisco's backyard. A move would be a financial windfall for the A's, and the Giants know it. San Jose is the tenth-largest city in the United States (Oakland is ranked 45th, somewhere in between Omaha and Tulsa). San Jose also just happens to be the so-called capital of Silicon Valley, the tech-center of the universe. There are mammoth corporate dollars there, most of which are currently spent with the Giants, from luxury suites to marketing agreements with Yahoo! and Oracle.

STADIUM ISSUES:

When folks walk through the turnstiles at ballparks throughout the country, they're not coming to just see a game. They're coming to see the ballpark itself and enjoy the experience. Fenway Park has its iconic Green Monster. Ivy lines the walls at Wrigley Field. AT&T Park in San Francisco has four giant slides through a Coke bottle. Safeco Field in Seattle serves up a $10 "ichi roll."

The A's home field? Any atmosphere at the Coliseum has been stripped away by Mt. Davis, the infamous cluster of seats created solely for the A's co-tenants, the Oakland Raiders. The A's now have themselves a dilapidated multi-sport stadium that is more suited for football than baseball. It's the fifth-oldest ballpark in baseball, and not in a nostalgic Dodger Stadium kind of way.

Which is why

the A's are fighting like hell to build a new ballpark which could bring in $100 million in additional revenue every year. They tried Fremont. The deal fell through. They've talked about a new stadium in Oakland, but the city and the team can't seem to find a place that suits both of their needs. Short of relocating to San Jose, Portland, or Las Vegas, it looks like the A's are stuck.

The A's, simply put, are playing in a game that is rigged against them. They play in an undesirable city playing second fiddle to a team that controls an otherwise booming market. They're stuck in an armpit of a stadium. The team is seeing pennies on the dollar from those fans who choose to watch games on TV. Despite all of this, the A's would at least have a puncher's chance if there was a salary cap to bridge the gap between them and the Yankees.

At some point, you would understand if the A's just threw their hands up and quit. Yet, they fight on. The year before I started writing this new book, Oakland managed to win the AL West with 94 wins.

Moneyball was about a small group of undervalued professional baseball players and executives. Outcasts, misfits, and rejects who had turned themselves into one of the most successful franchises. That story continues, but it also has changed. Now new challenges await the underdogs. And I can't wait to tell their story. Again.